After meeting with Wally Bahoum at Lamin Lodge, we wondered if the batiks from Indonesia have anything to do with the African batik. We found two intriguing stories. Find out which one you like most. And of course… check out Peter’s new outfit!

African style Batik: is the origin Dutch?

Lots of the fabrics we see in West Africa nowadays are not made by African firms.

Some African designers even refuse to use African wax prints, because they see them as a legacy of colonialism. What is the story behind this?

Indonesian origin, English recording, Dutch design and print, and a global trade of Batik

The English documented the batik making process in Indonesia in the 19th century. This was at the time that the British captured the island from the Dutch. Sir Raffles explained how the Indonesians passed hot wax through a tube to draw designs on fabric. After that they dyed, re-waxed and dyed the fabric again for up to 17 days.

When the Dutch ruled Java again, they used his book. They worked out how to mechanise the process so it would be cheaper than the expensive hand-made batiks. The Dutch continued exporting their wax prints to the region for the next 22 years.

Why did Dutch textile become popular in West Africa?

Well, the Dutch were expanding their colonies with the help of soldiers from West Africa. When these soldiers returned to West Africa, they took the Dutch-manufactured batiks with them. And from that moment, there was a growing demand for these wax prints in West Africa. The material was easier for sewing machines than the thicker locally woven material. They also had some similarities with the West African traditional local tie-dye.

So, some of the ‘West-African’ prints were actually designed in the North-West of Europa and most of them are now produced in the Far East, because production costs are lower there.

African style batik: The authentic Gambia’s Batik Art.

Ever since the Gambians coloured cloth with fermented mud, they have made special designs for their fabrics.

This documentary shows the traditional tie-dye process in the Gambia

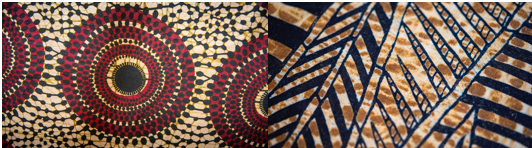

Gambians carved inspiration of the land and the river in wood, or they painted it in mud, stamped with wax and dyed the fabric. Originally, they dyed the fabric with mud. Or with the colour from Kola nuts, which is a deep orange or reddish colour. Or with indigo, making a deep blue colour.

The industrial dying products are now used more often because they are cheaper and more practical.

Batik can be simple using one colour. It becomes more difficult when you add a second or third colour, and you vary the pattern of stamps. A special technique is a form of dripping where you take a paint brush, dip it in the hot wax, then let the wax drip on the cloth to make a pattern of dots. You can dip the cloth in many different colours, creating a beautiful effect. And you can coat the entire cloth in wax and then roll and crack the wax, creating wavy lines throughout the fabric. At Lamin Lodge we saw a combination of these techniques, which makes it stand out from the products tourists can find at the coast. Wally learnt Batik from his father and now adds his own touch to the design.

The maker can use stamps or templates to be able to produce dozens and dozens of batiks for the short tourist season. Or he can make unique, custom-made articles. He decides, using his knowledge, skills and inspiration to make the most beautiful batiks. This is authentic craftmanship, sometimes even art.

We are quite sure the unique handmade quality of Gambia batik, like we found in Lamin Lodge, cannot be replaced by factory work. And last but not least: this kind of entrepreneurship helps to build resilient communities.

Sources and further reading:

https://www.smcm.edu/gambia/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2015/03/art-and-survival.pdf