This is the third part of the article discussing the differences between nuclear energy versus renewables with batteries.

Here we talk the perception of two generations. The generation who experienced the Chernobyl disaster in 1984 and the generation later, experiencing the Fukushima disaster from 2011

Public opinion – Chernobyl

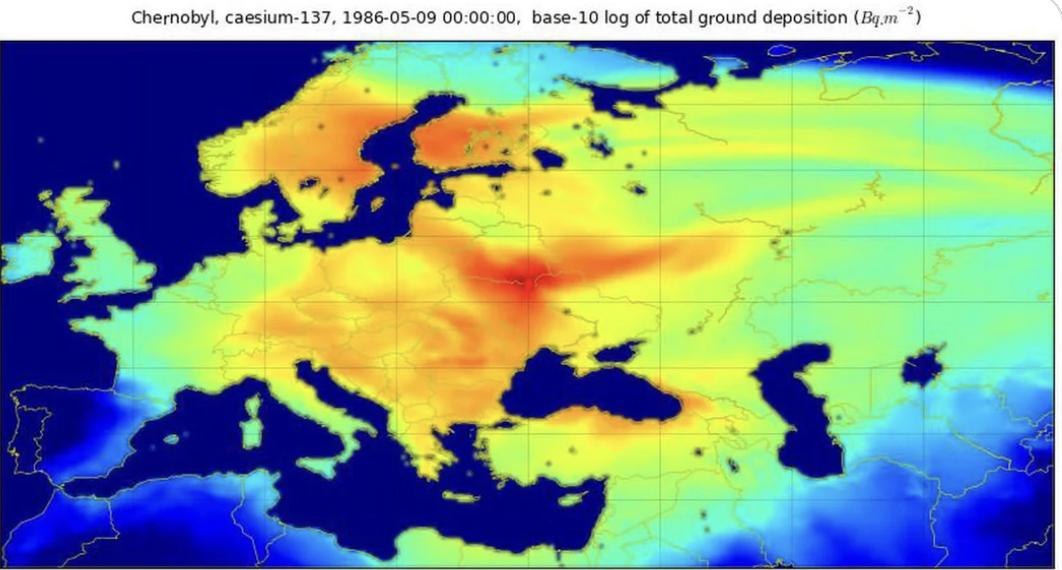

April 1986, Reactor 4 of the nuclear power plant in Chernobyl got a runaway. Despite the heroic actions of the Russian en Ukrainean firemen, a meltdown could not be stopped and a cloud of radioactive material was spread over Russia and Europe.

Since Gorbachev (then the leader of the USSR) executed the policy of complete transparency, all data were exchanged, and published by the media. So everybody was remarkably well informed. The generation that experienced this disaster, still doesnot want nuclear plants. But, the new generation?

Fukushima for the next generation

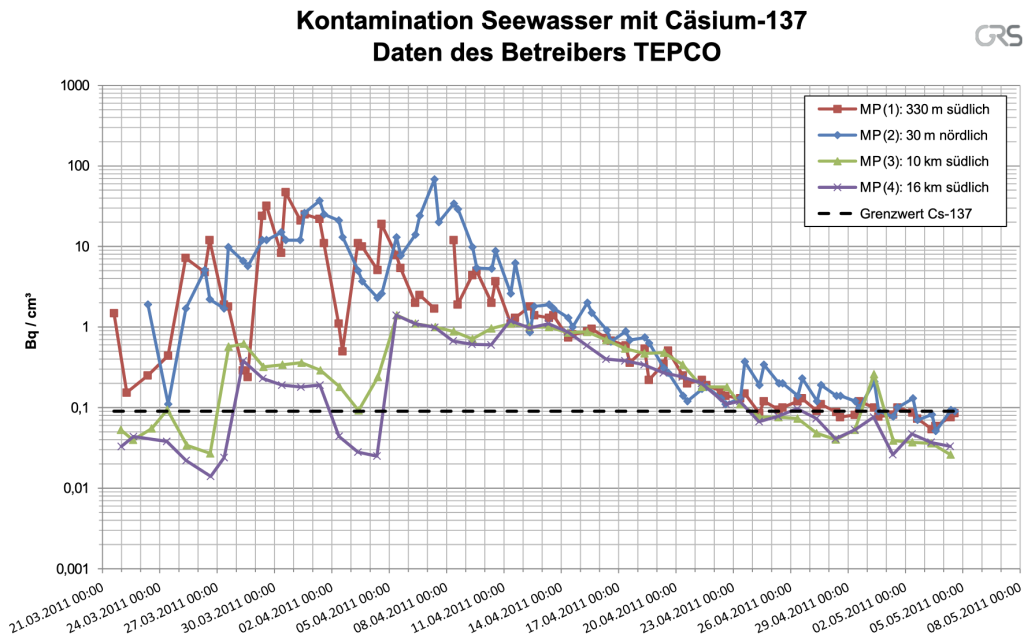

Accidents with nuclear plants, although never foreseen, always happen. So in March 2011, the so called ‘Millenials’ generation could experience one, in Fukushima, Japan. This accident was rated just as heavy as Chernobyl. The nuclear plant there, is situated in an area with a restless earth crest. Every some years there is an earth quake, sometimes with a tsunami. Therefore the plant was built extra strong, but both the earthquake and the following tsunami were stronger. The plant was serverely damaged. Fortunately, the operational crew could mitigate a lot, by continuously adding new water to the reactors, to cool it. This cooling had to be done for many days, and it was continued even after the evacuation of all workers, till the temperature of the reactors dropped.

Also here was a meltdown. Also more than thousand people were evacuated (which led to several deaths).

Still it was not that great world news. The company TEPCO and the government presented it as a serious incident, but not as a disaster. They reported that all contaminated water was still in basins, But in the meanwhile, they forbade the personnel to mention the word ‘meltdown’. Emails, read and unread, were consistently deleted (source).

The word ‘meltdown’ was first mentioned weeks after the accident, and most media treated this late news not as a front page news.

Journalists tried to get information from elsewhere and the they found was a retired engineer who worked on the design of the nuclear plant. But, he could not do much more than giving a variaty of possible options on what could have happened.

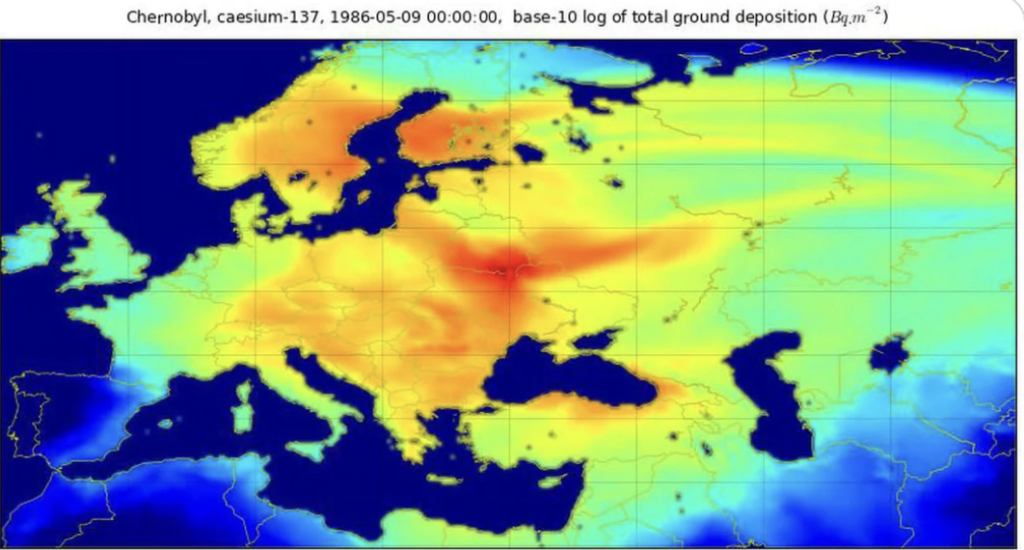

Again later, instead of containing it, all the contaminated cooling water was pumped from the basins into the ocean. The French IRSN this as “the most important emission of radioactivity ever observed”. There is a strong current along that coast, so the evidence dispersed quickly.

Conclusion

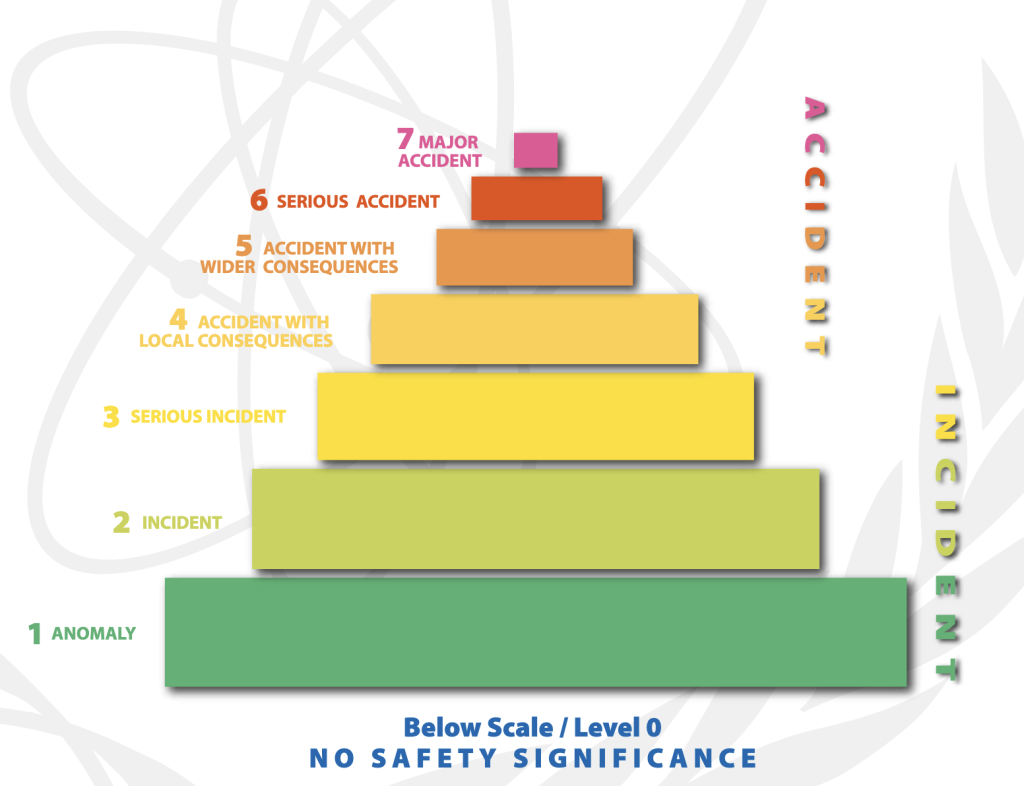

Chernobyl and Fukushima are both rated as severe accident, with a 7 on (source)

In contrary to the generation experiencing the Chernobyl accident, the Millenial generation was not fully informed about ‘their’ Fukushima disaster. The information was fragmented and spread over a longer time. This spinning didnot lead to thorough, comprehensive articles in the international media.

It also doesnot help that Japan is far away. The more distance, the less the news, is an old media rule. Third, because of that distance, there was no direct physical threat, like the contaminated air over Europe that poisoned our vegetables.

This made that the millenial generation did not become affected by ‘Fukushima’ . The result is that the younger generation has a lower awareness about the risks. So, a governement’s decision for the construction of a new nuclear plant is found hardly relevant.