We entered Suriname and saw sharp divisions in the water, probably differences in the currents of river water and oceanwater. And we found many more controversies in Suriname.

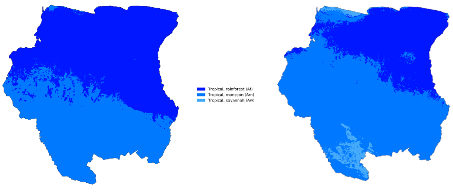

Since 2014, Suriname is one of the three countries in the world with a net-negative carbon economy. They absorb more greenhouse gases than they emit from human activities.This negative carbon output is easy to explain. Only half a million people live in Suriname. 90% of Suriname’s human activity is on the coastal strip of 30 kilometer. The other hundreds of kilometres are jungle, rainforest, which capture carbon.

Carbon negative, but necessary carbon productivity

Like we saw in Gambia, also Suriname is particularly vulnerable to sea level rise and salt water intrusion.[11] , because nearly all people live in the low lying coastal strip.

Agriculture and mining are the main sources of income. Agriculture contributes the largest part of the country’s emissions.[2], the mining is the next. The country is covered by forests, mainly pristine rainforest, which absorb the CO2. This annually absorbs 8.8 million tons of carbon, while providing annual emissions of 7 million tons of carbon

While Suriname is rightfully proud of its carbon negative status, it badly needs the income from mining: formerly bauxite, now oil and gold. Petroleum exports are an important part of the economy of Suriname,[7] much of which is controlled by the state owned Staatsolie Maatschappij Suriname. As of January 2020, an American corporation, Apache Corporation, was drilling wells in Maka Central.[8] Unfortunately, mining can do great harm to the rainforest.

Unfortunately, the building of the dam came with negative side-effects. The original inhabitants, the Samarakans (Marrons) were forced to move, the wood in their forest was cut and they suffered a great deal from all of this.

Suriname has an important source of reneweable energy: hydroelectric energy. In the 1960s, the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) built the US$150-million Afobaka Dam[16] . This created the Brokopondo Reservoir a 1,560 km2 lake, one of the largest artificial lakes in the world. Some 75% of the hydroelectric energy in the country was used for alumina and aluminium.(source). After the shutdown of Alcoa, Suriname became the owner of the Dam and hydroenergy now supplies the major part of the countries’ electricity (source)

Rich country, poor people

They say here: “You put your walking stick in the soil and next year there are branches and leaves on it”. That is the fertility. But the country is also rich in minerals. In 1990, the UN ranked Surinam as potentially the 17th richest countries of the world. On the other hand, the UN in 2018 predicted that in 2030 Surinam would be one of the poorest countries of the world pro capita.(source) This would probably be caused by the budget deficit, caused mainly by debts and the great number of governmental employees (source).

Now, Suriname is a low-income country indeed. Most people earn 260 to 400 Euro per month and prices of living are relatively high. In 2018 20% of the people lived under the poverty limit. With COVID, GDP dropped 15%. Like most of the Caribbean states. As a matter of fact, it goes for most of the developing countries who are at risk of flooding with climate change.

No contribution to climate change, but victim of the consequenses

Surinams contributions to global climate change have been limited. But now, climate change leads to warmer temperatures and more extreme weather events. Noel, the owner of the Marina, tells us that schools in the south of the country have been closed in recent months due to flooding.

According to the World Bank, temperatures have already increased across the country, with a significant increase in hot weather.[9] A large part of the rainforest may disappear because of the changes in rain and temperature.[10]

The future: long term or short term?

Suriname is in a constant balancing act in relation to sustainability. And it is aware of this.

In 2020 Suriname updated the Nationally Determined Contributions focus on four key areas; forests, electricity, agriculture and transport. Suriname wants to hold on to 93 per cent forest cover but needs “significant international support… for the conservation of this valuable resource in perpetuity.”

Sustainable and “clean” electricity is also a priority; Suriname strives for a “share of electricity from renewable sources above 35% by 2030.”

Agriculture is the cause of 40 per cent of the country’s total emissions but this has also provided a continuous valuable source of income. At the same time, the sector is strongly impacted by climate change. So, Suriname focusses on the development of climate-smart farming. That includes water resources management, the promotion of sustainable land management; and adopting innovative technologies, for example converting biomass into energy.

For transport, Suriname wants to improve public transportation and introduce controls on vehicle emissions.

It is going to be quite a road to combine economic and sustainability goals. Suriname is well worth the effort.

But in the meanwhile, what can Surinam do for such long-term ambitions? Still the state has a ‘waterhead’ on government, which in combination with prestige projects like the Wijdenbosch Bridge, led to a state debt. The pay back forms the largest costs each year. And still, the salaries have to be paid every term of the month, being the second largest costs.

Surinam needs foreign money, but their banks mostly block the ways to get it in.

A concrete example. Peter rented a car and payed with some left-over Euros. The rental man was very happy with it.

At the gas station Peter topped up the petrol tank. The gas station does not accept a credit card, only cash Surinam Dollars. So, Peter goes to the ATM for cash. Every ATM has a waiting line (otherwise they don’t work). Peter tried to get money from the ATM, but at the very end of the procedure, it says “No”. Peter tries his other card. This one does not work either, also at the very end. Only result is that the line gets longer. Peter tried other ATMs. No way.

Peter went to the bank. The line was 45 minutes. The answer was:

“Please try it later.” Peter tried it later with 5 other ATMs. Again, Peter went to bank, and was helped after 35 minutes. The answer was also here:

“Please try it later.” Peter said he already did. They answered:

“Please try it tomorrow.”

So, from 11 AM till 4 PM Peter has tried to get Surinam dollars, but zero success. He would have much preferred to spend this time to buy things, eat Surinam meals etc. That day Peter heard all the professional answers for: “we are too incompetent to get money from foreign bank accounts”. These unwilling ATMs are not an incident; it is structural.

Sources:

Like to join the ‘Ya’ on her sustainable cruises? mail info@fossilfreearoundtheworld.org